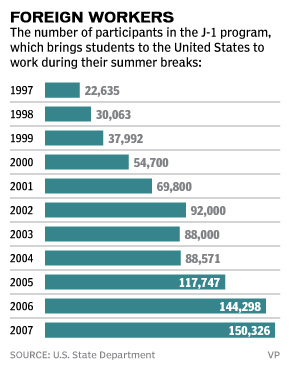

최근 미국에선 리조트들이 현지에서 조달하는 인력이 부족하다고 합니다. 그래서 최근엔 그부족한 인력들을 외국에서 구해온하고 하는데요 대부분 J-! 프로그램을 통해서 들어옵니다. J-1 비자는 지난 1961년에 미 하원에서 통과시킨 Exchange Visitor Program으로 생긴 비자 타입인데, 각국의 문화적 이해를 돕기위해 만들어진 프로그램입니다. 지난 10년간 J-1 "Summer Work & Travel" 과정으로 미국을 방문한 학생들의 수가 6배 이상 증가했습니다. 1997년에 22,635명이었던 방문자 수가 2007년엔 150,326명으로 증가했습니다. 자세한 내용은 원문을 참조 하세요 ^^

By Carolyn Shapiro

The Virginian-Pilot

© June 8, 2008

VIRGINIA BEACH

In mid-January, David Finwall took a whirlwind tour through Bulgaria, Turkey, Russia and Ukraine to find college students to work at the Oceanfront.

The human resources director knew he had plenty of "cool" attractions to offer them: the beautiful beach and ample sunshine, the vibrant nightlife and a prime East Coast location.

By the end of the two-week trip, he had hired about 250 foreign students to spend this summer working for Gold Key/PHR Hotels & Resorts, one of the city's largest hotel owners. Pursuing careers such as computer science and economics at home, they would come to Hampton Roads to cook food, carry luggage and clean toilets.

The students come to the United States on J-1 visas through the Exchange Visitor Program, which Congress created in 1961 to enhance cultural understanding between nations. In recent years, it has morphed into a major source of labor for many employers, particularly those in the hospitality industry.

Critics charge that the program has little oversight and contributes to illegal immigration.

Over the past 10 years, the number of students coming to the United States under the J-1 "summer work and travel" category has multiplied more than sixfold: from 22,635 exchange visitors in 1997 to 150,326 in 2007. Last year, 3,706 landed in Virginia Beach, according to the State Department, which administers the J-1 program.

Busch Gardens Europe, one of the region's first employers to embrace J-1, brought in 96 students to work for the Williamsburg amusement park in 1998. This year, it expects 663.

Gold Key - with seven beachfront hotels - also has grown more involved in the program, Finwall said. He took his first recruiting trip overseas to Thailand last fall, then Eastern Europe in January.

"We don't have people to do these jobs," Finwall said, citing low regional unemployment. "U.S. college students do not want to come and make beds and clean toilets for $7.75 an hour."

Dmytro Iershov

Dmytro Iershov said his friends at home in Ukraine might chide him for working as a housekeeper, but that doesn't matter to J-1 workers.

"Any job is good," he said.

Last month, he arrived in Virginia Beach for his second stint for Gold Key. The 20-year-old's passion is techno music, and he said he helps promote the genre in Ukraine and elsewhere.

He is serving tables this summer at Pi Pizzeria, hoping to memorize the long menu and earn enough in tips to visit New York, Miami and Detroit - key techno hubs. On Tuesday nights, he likes to hit Peabody's nightclub near the Oceanfront for the "Euro Explosion" with techno-spinning DJs.

This year, he's living with a few friends rather than packing into an apartment with a dozen students, which saved him money in 2007 but was so noisy it disrupted his limited sleep. He took a second job last summer to supplement his earnings as a serving assistant at Mahi Mah's restaurant at the Ramada on the Beach.

Most J-1 students seek second jobs to cover their program and travel costs. Such moonlighting is allowed by the program. Iershov spent nights cleaning restaurants for a janitorial service, earning $8 an hour and extending his workdays to 14 hours. That left little time for traveling.

"Last year, I made a mistake," he said, "because I found two jobs and didn't have time to do anything."

Employers like the J-1 because it has fewer restrictions than other foreign labor programs. There is no cap on the number of visas granted, and companies don't have to prove that they cannot find U.S. employees to fill their jobs.

The foreign students typically earn the same hourly wage as their U.S. colleagues - around $7 or $8 an hour for most of the jobs. Employers don't provide health insurance - nor Medicare or Social Security - for J-1 workers, which saves some money. They must adhere to minimum-wage and workplace safety laws.

The program does have a time limit. The summer work and travel visa allows students to come to the United States only during their summer break from school and stay only four months.

But foreign students are available year round, depending on when their break occurs. Europeans come during our summer, Asian students in the spring, and South American workers in late fall and winter.

U.S. college students often have tighter summer work windows, either finishing school in June or returning in August. Young Americans who might have taken these jobs in the past also have more options now for internships or white-collar positions in their fields of study, said William Mezger, an economist for the Virginia Employment Commission.

The Gourmet Gang has hired about a dozen J-1 workers for the past two years, said Mahi McCauley, area manager for the catering company and chain of local bistros. Many American job applicants, she said, dress unprofessionally, yawn through interviews or quit after a day or two of work.

The foreign students have a better attitude, McCauley said.

"They work very, very hard," she said. "And they are respectful."

Like most J-1 students, Oksana Dynka heard about working in the States from friends and classmates in Ukraine. An economics student at a polytechnic university, she said she wanted to meet Americans, make new friends and see the world while still single and unfettered.

She signed up for her visa at a Star Travel office and chose Virginia Beach from a list of locations and jobs on a Web site. Dynka met some of her Gold Key co-workers while waiting at a U.S. Consulate's office in Ukraine. During her interview there, she answered benign questions about her parents and what she ate for breakfast.

Last month, she and five other J-1s flew to New York and rode a bus the next day to the Greyhound station on Laskin Road. As they rolled their luggage down the street, a man offered them a place to live.

Dynka, 20, is working in the banquet area of Mahi Mah's. She isn't sure whether she'll give up her free time for a second job.

"Money isn't the most important thing for me," she said. "We come here for vacation."

The program is priced like a vacation, too. Dynka paid about $2,000 to cover her visa paperwork, travel arrangements and other fees. The travel agencies partner with one of 56 State Department-approved sponsors for the summer program.

Every J-1 visa holder needs a U.S. sponsor. Students typically pay $2,000 to $3,000 to their travel agency, which in turn pays the sponsor. Students pay sponsors more to be pre-placed with an employer.

Sponsors sell the students the health insurance they need to work. Employers pay the sponsors nothing, but sponsors rely on them to offer jobs that attract more students.

The nonprofit Council on International Educational Exchange is one of the largest sponsors, bringing in more than 30,000 students a year, said Phil Simon, the agency's vice president of employer relations.

In the summer work and travel program since 1969, the council sponsors students for many of the region's major employers, including Gold Key and Busch Gardens. It listed $23.5 million in revenues on its 2005 tax filing, the most recent available on the GuideStar database of nonprofit organizations.

Sponsors bear responsibility for the students while they're in the United States, including for their safety, their employment and their behavior, both on the job and off. But every year, Gold Key's Finwall said, he fields complaints from workers who have had no contact with their U.S. sponsor.

No sponsors have offices in Hampton Roads. The nonprofit council has field agents in several cities, the closest in Philadelphia, Simon said. The agency keeps in touch with students via e-mail and operates a 24-hour hot line to address workers' or employers' concerns.

Back home in Ukraine, Valeriya Peltek and Lyudmyla Dobrovolska study international relations. Dobrovolska, 22, speaks Arabic and Bulgarian, as well as Ukrainian and English.

In Virginia Beach, they're taking orders at the cash register and drive-through window at a McDonald's on Shore Drive and Great Neck Road. Dobrovolska spent last summer as a J-1 at an amusement park in Alabama and wanted a beach location this year. Peltek saw the program as a chance she wouldn't otherwise have to see the States.

"It wasn't my dream to work in McDonald's," Peltek, 19, said with a laugh. "But we knew. We knew what we were signing for."

The Ukrainian visitors didn't know they'd end up so far from the Oceanfront with nowhere to live. Housing is a problem for J-1 workers, particularly in resort areas with few affordable rentals.

Neither sponsors nor employers have an obligation to provide housing for the students. Janus International Hospitality Student Exchange, a J-1 sponsor based in Doswell, leased an old motel in Williamsburg to solve the housing issue for the workers it brings for several employers there.

When Dobrovolska and Peltek arrived in late April, they dropped their bags at a motel and went looking for the McDonald's. Wandering up to 77th Street, they asked directions from a local couple out for a stroll. Bill and Judy Marx took pity on the students, brought them into their North End home, ferried them around the region, and got them bikes to ride to work.

"It doesn't seem right to have all these people come in and not have a place for them," Judy Marx said.

Unhappy students may not change prearranged employment without their sponsor's permission. Some leave their jobs anyway, violating the visa terms.

If caught by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, those students could face immediate deportation and be denied future entry into this country.

That also goes for students who fail to return home after four months. Those who want to stay in the States are required to go home first and apply for a different visa, though some do hire lawyers while they're here to adjust their status.

In an October 2005 report, the U.S. Government Accountability Office concluded that the State Department lacked sufficient oversight of the J-1 work and travel program and its participants. The GAO said the Department of Homeland Security had incomplete data but that, among the J-1 visa holders it tracked, it found that 24 percent might have stayed past their deadline.

J-1 students have remained in Hampton Roads after their visas expire. Some return legally under a different visa. Others have married, obtaining a "green card" to live and work as noncitizens. In April, federal authorities cracked down on marriages deemed fraudulent, charging 33 people, including some Eastern European students who came on J-1 visas and married Navy sailors.

"It isn't being used for its intended purpose," said Greg Schell, an attorney who specializes in other visas for the Migrant Farm Worker Justice Project in Lake Worth, Fla.

"It has become this labor program with no oversight," he said, citing its cultural intent. "There's nobody watching."

But employers increasingly champion J-1. And not just because they need to fill jobs, said Gold Key's Finwall.

During his January recruiting tour, Finwall said, a particular Ukrainian student's letter left an impression. The young man, studying economics and law, described how his "rich experience" in America would help him reach his ambitions.

"It's the passion for self-improvement. It's the positive desire for new experiences," Finwall said of the student.

"That kind of passion and that kind of personality, that's the kind of person I would hire any day."

참조: http://www.goabroad.co.kr/ic/area.html?Qplace=&searchkey=&searchvalue=&page=1&board_seq=1368&mode=read